Quick Hits: Today’s Top Stories

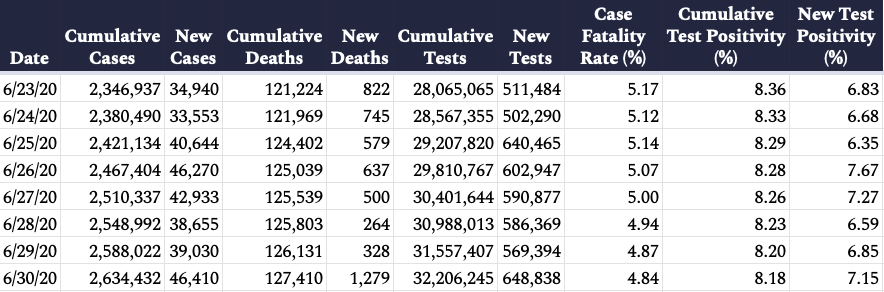

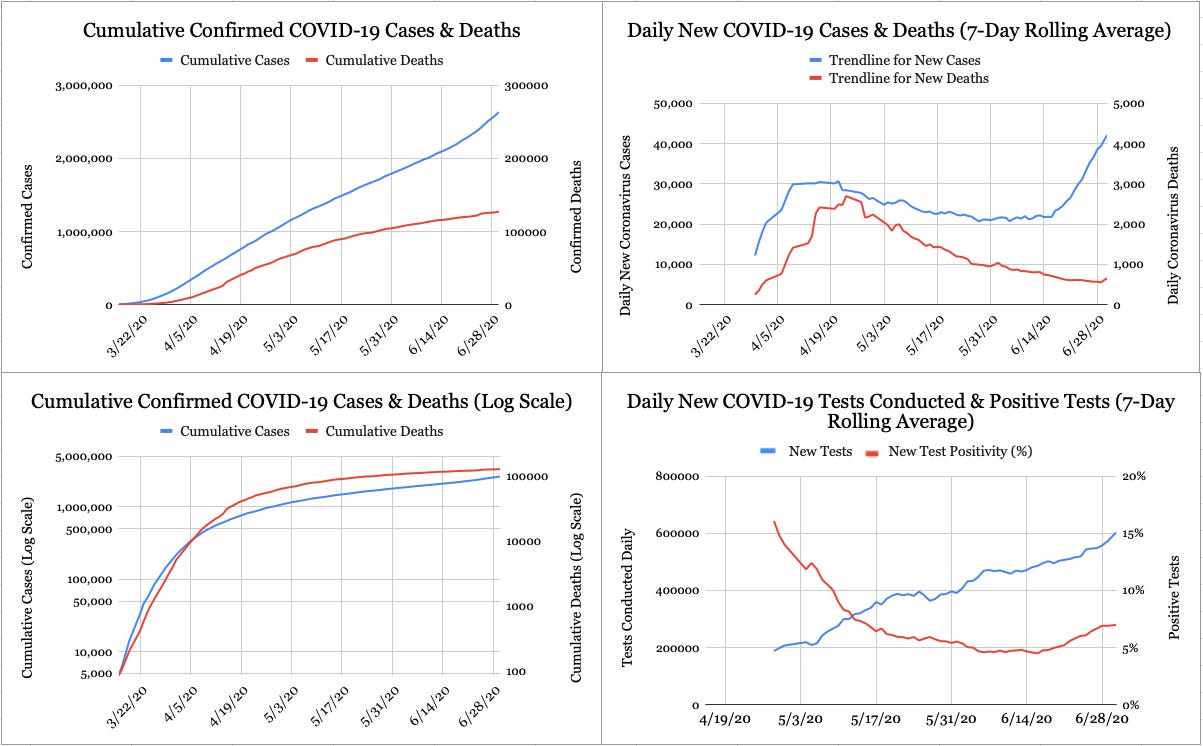

- As of Tuesday night, 2,634,432 cases of COVID-19 have been reported in the United States (an increase of 46,410 from yesterday) and 127,410 deaths have been attributed to the virus (an increase of 1,279 from yesterday), according to the Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 Dashboard, leading to a mortality rate among confirmed cases of 4.8 percent (the true mortality rate is likely much lower, between 0.4 percent and 1.4 percent, but it’s impossible to determine precisely due to incomplete testing regimens). Of 32,206,245 coronavirus tests conducted in the United States (648,838 conducted since yesterday), 8.2 percent have come back positive.

|  | |

|  | |

- Dr. Anthony Fauci testified in a Senate hearing yesterday that the United States may begin to see up to 100,000 new coronavirus cases daily. “I can’t make an accurate prediction, but it will be very disturbing, I will guarantee you that,” he warned.

- The European Union will officially reopen its borders today to residents of 15 countries the bloc deemed to have the coronavirus pandemic under control. The United States is not on the list.

Are COVID Surges Attributable to the Recent Protests?

Over the last month, the two biggest stories in America have been the anti-racism protests sparked by the death of George Floyd and the rapid resurgence of COVID-19 following two months of the virus slowing. The obvious question linking the two: Have weeks of mass assembly and protest been an accelerant to viral transmission?

It’s been difficult to drill down on this question, in part because of accusations of politicization and fuzzy data collection. New York City and San Francisco, for instance, have opted not to have their COVID contact tracers ask potentially infected people whether they attended a protest—a strategy that has undoubtedly made the relationship between protests and the pandemic harder to suss out.

Nevertheless, enough data has trickled in to give us a rough idea of our answer. Based on what we know now, while the George Floyd protests may have presented an increased infection risk to the protesters themselves, it seems they haven’t yet caused broader infection spikes in the cities in which they took place.

Let’s unpack this a little. To begin with, there’s the fact that many protesters have taken steps to cut down on transmission—maintaining some level of social distancing even in a crowd, wearing masks, and, most critically, protesting outdoors, where passing along a critical load of the virus is far more difficult.

This is the reason most frequently cited for why many hoped the protests would not lead to case spikes, but it’s not a sufficient explanation in itself. After all, as any epidemiologist would tell you, all these precautions are simply a matter of managing risk—they might limit spread within a group, but there’s no guarantee they can prevent it.

Sure enough, the data from those cities and states that have kept tabs on infections at protests shows that in many cases some transmission was in fact taking place. In Boston, 400 protesters later tested positive for COVID. In Houston, police officers reported increased cases among their ranks after the protests. And in South Carolina, demonstrators cut off in-person protests early after 13 demonstrators tested positive for the virus.

And yet many of the cities that experienced the biggest protests, like New York, Philadelphia, and Minneapolis, have seen no major changes yet to their former coronavirus trajectories. The city of San Francisco might not be keeping track of protest attendance in its contact tracing, but Alameda County, which includes many of its suburbs, is asking those questions—and county officials say the protests are “not emerging as a risk for the most recent cases that we’re seeing in the county.”

So what gives here? The missing link here appears to be in the behavior not of the protestors but of everyone else. These mass protests didn’t begin back in April, when most of the country was still hermetically sealed away, but in June, when it was already well on its way to reopening. The protesters were the ones making headlines, but the whole country was already beginning to get comfortable mingling again.

Or at least they were getting comfortable, until the protests started. For many, the prospect of major civic unrest proved just as powerful an inducement to stay at home as the virus itself had months before. According to a fascinating new study of cellphone data in 300 U.S. cities from the National Bureau of Economic Research, this actually meant that social distancing increased on the whole in cities with major protests during the days when those protests were at their fiercest.

This one-two punch—that protests may have raised the risk of infection among the marchers but indirectly lowered it in their communities more widely—has been garbled in some press reports, which have erroneously suggested that it demonstrates no link between protests and the pandemic at all. This is both misleading and decreasingly true: Although the protests are ongoing, the major social unrest that accompanied them for much of June has largely subsided. Going by the logic of the NBER report, this would suggest that ongoing protests could be more likely to have a net positive effect on new infections.

On the other side of the coin, some commentators have pointed to the relative youth of many new COVID patients as a strong indicator that protests, overwhelmingly constituted of the young, may have played a major role in the latest surge. There may be something to this—but experts we spoke to point out that young people are also likeliest to be participating in high-risk activities like socializing at bars. As Dr. Anthony Fauci testified yesterday in Congress: “Bars, really not good. Really not good.”

While there are undeniable partisan pressures to think of the latest round of COVID transmission as being simply due to protests or simply due to increased economic activity, the reality is that these things likely feed into one another. One place where the disease has taken off in recent days is Atlanta, a city that was racked by protests and is in a state that was one of the earliest in the nation to begin the reopening process. To suppose there wasn’t some overlap beggars belief; it isn’t as though America is made up of those who protest police brutality and those who get drinks with their friends.It’s the exponential logic of infection: Bars may be more dangerous than protests, but the more bar infections take place, the more dangerous protests will get, and the more protest infections take place, the less safe anyone will be at a bar. |