8:04 am | May 23, 2019 | Go to Source | Author:

AS SHE SAT on the concrete steps outside Easton Stadium, her bright blonde hair wrapped in an oversized bow and a black bat bag slung over her shoulder, Stevie Wisz began to accept the obvious: She wasn’t going to play softball for UCLA.

Three times now she had arrived on the stadium steps for her tryout and all three times no one from the UCLA program had shown up.

“I was over it,” she said. “Embarrassed. I just wanted to leave.”

Her first five months as a UCLA freshman had been a nightmare. After growing up three hours north in the rural town of Orcutt, she felt like she didn’t fit in Westwood. She had struggled to make friends, often sitting in quiet corners of campus sobbing, wondering how she could have been so wrong about the only school that had ever felt right.

This was UCLA, the place that saved her life, after all. Softball was the game that had given her purpose. A self-described “mediocre” high school player, she had never played elite travel ball. But that hadn’t stopped her from pestering the Bruins’ coaches with emails begging for a tryout. They agreed. But now they had stood her up three different times. As she got up to leave, she heard a voice on the stadium concourse.

“Stevie?” the voice said. “Is that you?”

THE PEDIATRICIAN APPOINTMENT began like any other checkup for a 1-year-old. Measurements for height, weight and head circumference. But when the doctor placed his stethoscope on tiny Stevie Wisz’s heart, he didn’t like what he heard. “Weird,” recalls Melissa Wisz, Stevie’s mom. “He said it sounded ‘weird.'”

X-rays revealed Wisz had an enlarged heart. The doctor immediately sent Stevie and her mom to a pediatric cardiologist 40 miles away in San Luis Obispo. It was a dreadful coincidence. Two months earlier, Melissa’s 17-day-old son, Hunter, had died at that same hospital because of complications from Potter syndrome, a rare birth disorder. Now she found herself rushing to the same hospital with her daughter because of a heart issue. “I just remember thinking, ‘What is going on, God? Please don’t do this to me again,'” Melissa said.

In San Luis Obispo, doctors diagnosed Stevie with aortic stenosis, the severe narrowing of the aorta as it branches out from the heart. Stevie’s aortic valve was one-sixteenth the size it should have been. With such a narrow passageway, much of the blood her heart was pumping was leaking back into the heart chamber, meaning her heart had to work that much harder to pump blood throughout her body.

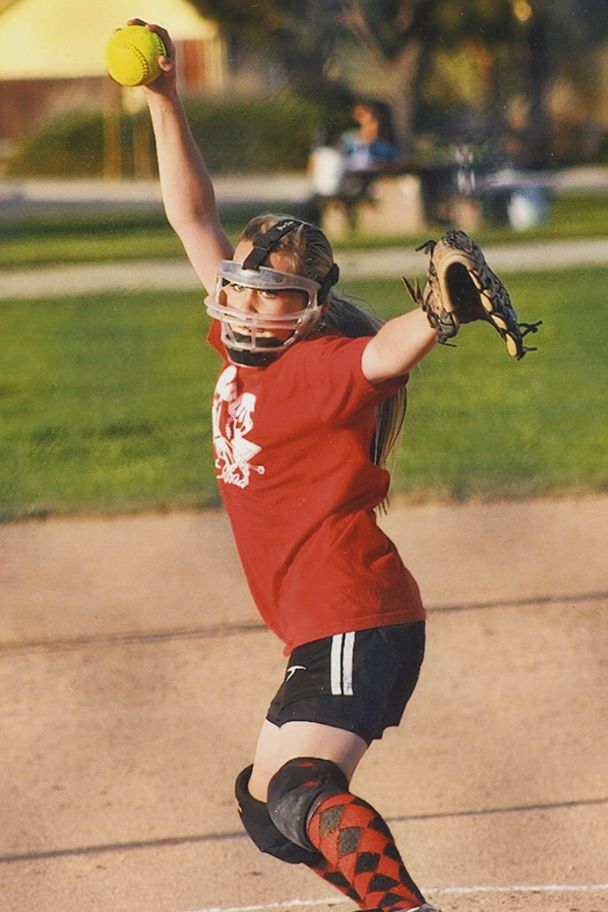

Wisz would eventually need open-heart surgery to save her life. But the doctors suggested postponing the surgery as long as possible to allow the heart to grow closer to its full size. They would keep an eye on Wisz through regular checkups. Over the next several years, she lived like many other little girls, competing in soccer, basketball and track. In a fourth-grade track meet, she remembers running as hard as she could but finishing a distant last. “That was the first time I remember thinking I was different,” she said.

When Stevie Wisz finished last in a fourth-grade track meet, she realized something about her was different. Courtesy Wisz family

Over time, the blood leaking back into her heart went from a mild problem to moderate to severe. By the summer of 2006, after fourth grade, doctors said it was time for surgery.

On that August day at UCLA Medical Center, nurses pushed 9-year-old Stevie’s stretcher to the operating room as her mom and dad walked alongside her. Melissa squeezed Stevie’s hand. A nurse promised to call with updates. They said goodbye. The stretcher rolled through the double doors. And she was gone.

For nine hours, the Wiszes tried to keep their minds occupied. It was impossible, especially with the updates. The first incision. The cracking of the breastbone. The heart-lung machine. In the operating room, doctors discovered Stevie suffered from heterotaxy, a birth defect that created a hole between the chambers of her heart. They repaired that in addition to cleaning and widening her aortic valve.

The surgery was successful, albeit a temporary solution. In a few years, she’d need another open-heart surgery to insert either a pig valve or an artificial one into her aorta. And doctors told her she could no longer play soccer, basketball or any other sport requiring endurance. She focused on softball.

“If you were to look at me, you never would have known what was going on,” she said. “But I knew. I was so self-conscious and insecure. Sports was my life. I had to play something. I wanted to prove I could do it.”

AFTER HEARING HER name that day on the Easton Stadium stairs, Wisz stood up and met UCLA team administrator Claire Donyanavard. Donyanavard escorted Wisz up a back ramp to the field, where a handful of UCLA players gathered before practice. Assistant coach Lisa Fernandez and head coach Kelly Inouye-Perez introduced themselves. Inouye-Perez took one look at Wisz in her hair bow, nose ring and purple “W” visor from high school and offered a few suggestions.

“First thing she ever said to me,” Wisz said. “‘We don’t wear bows here. We don’t wear nose rings.’ And then she told me to take off my visor because she thought it was a Washington visor. They handed me a UCLA hat. I was so intimidated.”

Fernandez sent Wisz to join a hitting group facing pitcher Selina Ta’amilo. Then she put her in the outfield, peppering balls from left to right, forcing Wisz to sprint back and forth to show her tracking abilities. Fernandez then timed Wisz running the bases. When the tryout was over, Fernandez said she’d be in touch. But an impression had been made.

“She wanted to truly represent the people who gave her life. ”

– Lisa Fernandez

“She just had this ray of light,” Fernandez said. “The brightness in her eyes, on her face. The smile. The positive energy. Anyone who has ever met her knows she has this great presence. Then you hear her story and it was just like, ‘Wow, what can this kid potentially do for us?'”

Wisz’s answer was simple: Whatever they wanted. She’d be a manager. A practice player. She’d feed balls into the pitching machine. Cut game film. Shag fly balls. Whatever. A few days later, UCLA invited Wisz to join the team as a practice player. She agreed, but before and after practice, she wouldn’t go into the players’ clubhouse. “I was so awkward,” she said. “The girls must have thought I was such a weirdo.”

“She was so worried about overstepping her boundaries,” said Kylee Perez, a former UCLA All-Pac 12 infielder. “I’d literally have to go out there and get her, tell her she’s part of the team. ‘Come hang out with us.'”

Wisz didn’t travel with the team for the opening tournament of the 2016 season in Texas. But after several Bruins contracted food poisoning that weekend and the team was left without a pinch runner, Perez approached Inouye-Perez about adding Wisz to the roster. The following week, 20 minutes before the team bus left for a tournament in Palm Springs, doctors medically cleared Wisz to travel and officially join the team.

“My uniform was like an extra-large. We had to triple-roll my pants,” she said. “But I didn’t care.”

Stevie Wisz went swimming with dolphins on her Make-A-Wish trip to Florida when she was 9 years old. Courtesy Wisz Family

LATE IN THE summer of 2007, a year after Wisz’s first open-heart surgery, Stevie and her mom were shopping for back-to-school clothes when Melissa Wisz’s cellphone rang. Three days earlier, doctors had asked Stevie to wear a 24-hour heart monitor to keep an eye on her progress. The data revealed Stevie’s heart was stopping multiple times a night, for as long as nine seconds at a time. Doctors implored Melissa to get Stevie, then 10, to UCLA as soon as possible so doctors could install a pacemaker.

“I would hear her coughing all the time at night, but never really thought anything of it,” Melissa said. “Turns out that was her body rebooting itself.”

Steve Wisz, Stevie’s dad, packed a bag and raced to the strip mall to pick up his wife and daughter. They sped to UCLA, where nurses again rolled Stevie into the operating room so doctors could install a pacemaker. It had nothing to do with her previous operation or her condition.

“No one is ever prepared for a phone call like that,” Melissa said. “It was basically bad luck.”

Five years later, when Wisz was 15, the leakage in her aorta again became severe, forcing another open-heart surgery. This time, her heart was large enough that doctors could install a pig valve to improve the blood flow. It was a 13-hour procedure. She was older, wiser. She understood the risks. “I cried all the way down to the hospital,” she said.

But each trip to UCLA Medical Center brought with it a trip to the bookstore for new UCLA swag. And further confirmation that she would one day be a Bruin herself.

“It was never a question,” she said.

After the surgery, Wisz spent seven days in intensive care recovery. During one of those days, she suddenly couldn’t breathe. She began coughing uncontrollably. Gasping for air, she sat straight up in her bed and looked at her mom for help. Buzzers and alarms went off. Doctors and nurses sprinted into the room, knocked Wisz out and placed a tube down her throat to suck out the phlegm that had clogged her passageway. One of her lungs had collapsed.

“She had such a look of fear in her eyes,” Melissa said. “I was so scared. And I just kept thinking, ‘What else are they going to put my daughter through?'”

Wisz would return to school in a wheelchair and, over a span of several months, eventually make a full recovery. Doctors told her the new valve would last 10 to 12 years. But it would survive barely half that long.

Powered by WPeMatico