6:04 am | March 19, 2019 | Go to Source | Author:

It’s a game that might easily be forgotten. There are only 786 spectators at Webster Bank Arena in Bridgeport, Connecticut, on Jan. 10 to see the Fairfield (4-10) men’s basketball team host Saint Peter’s (4-11) in a MAAC conference game.

Most of the fans have no idea who the elegantly dressed assistant coach on the Saint Peter’s bench is. John Morton looks over the Fairfield roster sheet and notices all the different homelands of the players: Egypt, Sweden, Lithuania, Democratic Republic of Congo, Serbia, Tunisia, Puerto Rico. “I guess you could say we helped to start it all,” he says.

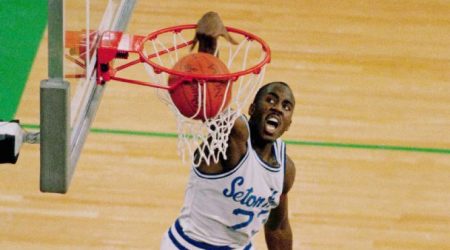

In 1989, John Morton was a member of one of the first NCAA basketball teams with an international flavor. The Seton Hall Pirates had Andrew Gaze of Australia, Ramon Ramos from Puerto Rico, a bench player who was Portuguese and a freshman walk-on whose father was from Argentina.

Oh, by the way, John Morton wasn’t just any member of the team.

“I’m often tempted to tell people who John is,” says Saint Peter’s athletic director Bryan Felt, himself a former student and administrator at Seton Hall. “Hey, do you know that man scored an NCAA Final record 35 points? Do you know that he helped put Seton Hall on the map?”

And that wasn’t just any Final. It may have been the most memorable game in the history of the tournament. Seton Who? wasn’t supposed to be playing Michigan in Seattle’s Kingdome to begin with, and to end the way it did…

Well, they’re still talking about the foul call at the end of overtime, and the inbounds pass from Ramos to Daryll Walker, and his desperate shot at the buzzer, and the graceful way coach P.J. Carlesimo and his players handled themselves after the heartbreaking 80-79 loss. The fairy tale was denied but, if anything, the legend of Seton Hall’s journey to the Final, a journey defined by two very different huddles, is even more compelling than a plain old Cinderella story.

For now, though, Morton and Saint Peter’s head coach Shaheen Holloway — Seton Hall ’00 — have another game to coach. And wouldn’t you know, it comes down to the final seconds. Trailing by three as the clock ticks down, senior Samuel Idowu launches an off-balance three from about the same spot on the floor where Daryll Walker took his shot. It misses, just like that shot 30 years ago. Fairfield 60, Saint Peter’s 57.

When asked if Idowu’s shot reminded him of Walker’s, Morton smiles and says, “I’d have to go back and watch them both.” Then he winks. “I’ll pass.”

You can go ahead, though, and watch the end of the April 3, 1989, game, which was broadcast that Monday night on CBS and called by Brent Musberger and Billy Packer. It’s readily available on YouTube.

You’ll marvel at Morton’s smooth three-pointer that tied the game at 71 with 24 seconds in regulation. In overtime, Gaze nails a big three. Carlesimo, dressed in tie and tan sweater vest, tries to nurse a 79-76 lead after Morton hits another three-pointer to give him 35 points. But the Wolverines, with future NBA first-rounders Rumeal Robinson, Glen Rice, Loy Vaught and Terry Mills, keep battling…

You might even yell at the screen when referee John Clougherty calls a foul on Gerald Greene, who barely touches Robinson on a drive to the hoop with 0:03 on the clock, and the Wolverines trailing by one, 79-78. Robinson goes to the line for a one-and-one. He was not a good foul shooter. But he makes them both — then and now.

Carlesimo calls a timeout. Michigan coach Steve Fisher counters with his own timeout after he sees what the in-bounds play might be: Ramos throwing a long pass downcourt from the baseline. With Mills now in front of him, the Seton Hall center flings it toward the other basket. The pass drifts off to the left, where Walker catches the ball over Greene’s hands, then pivots and makes a valiant shot from 25 feet… it caroms high off the backboard and bounces away as the Michigan players swarm the court.

While Musberger proclaims, “The Wolverines win the NCAA title over Seton Hall, a tough opponent all the way,” Carlesimo goes over to shake the hand of Fisher, who was handed the reins of the team just a few days before the tournament.

As “The Victors” celebrate, CBS switches to a tableau of the Seton Hall players in a huddle. The camera angle, pointing up from the floor, shows a collection of young men who are obviously disappointed but proud of what they had accomplished. They seem to know this will be their last time together. Then they break and go shake the hands of the Wolverines.

Looking at that huddle from the perspective of 30 years, you can’t help but wonder where that grace under torture came from. “P.J. had something to do with it,” says Greene, the point guard they called The General. “But mostly, it was us. We came a looonnnng way to get there. We knew we were one helluva team.”

Even in mid-winter, the Seton Hall campus in South Orange, New Jersey, has its charms. Named for Elizabeth Ann Seton, America’s first saint, the school was founded in 1865, which makes it the oldest diocesan college in the United States. The motto is Hazard Zet Forward, Norman French for “Despite Hazards Move Forward.” Not far from University Green is the Richie Regan Athletic Center, which now enfolds Walsh Gymnasium, where the Pirates played most of their home games in 1988-89.

The trophy Seton Hall won as the 1989 NCAA runner-up is in a glass case in the corridor alongside the gym, and so are tributes to the members of the Hall of Fame. The entire 1988-89 team was inducted five years ago, but there are also special plaques for Carlesimo and Morton and Ramos and Mark Bryant, who helped take them to their first NCAA tournament the year before. There’s also a plaque honoring Robin Cunningham, the first player to score 1,000 points for the women’s basketball team, which she did while playing No. 1 singles for the tennis team.

What it doesn’t mention is her role in that miraculous season. But if you saw Cunningham, who is now the dean of freshman studies, and Carlesimo hug on the court between their interviews for ESPN on this February day, you would sense how much they meant to each other, and to the school.

Carlesimo was just 32 when he first came to Seton Hall after being hired by AD Richie Regan. But P.J. was born to coach… and for a Catholic institution. He was the eldest of Pete and Lucy Carlesimo’s 10 children. Pete had played football at Fordham with Vince Lombardi, then became the football, basketball and cross country coach at the University of Scranton before taking over as the athletic director at Fordham. He was also the tournament director for the NIT and a wonderful raconteur. He was so entertaining, in fact, that he was once booked for “The Tonight Show starring Johnny Carson.”

P.J. was a chip off the old block, athletically and personally. He himself had played in the ’72 NCAA tournament for Fordham and Digger Phelps, then became an assistant coach there — he once coached a JV player named Denzel Washington. “He was studying acting, so we used to have to wait for his shuttle van to come up from Lincoln Center to The Bronx,” P.J. recalls. He then took over the program at New Hampshire College, and that led to the head job at Wagner College on Staten Island.

But Carlesimo would need more than charm to turn around Seton Hall. The Pirates had joined the Big East in 1979 only because Rutgers had passed, and then-coach Bill Raftery quickly discovered they were in over their heads. (If nothing else, Seton Hall produced outstanding basketball talking heads: Dick Vitale was Class of ’63.) Carlesimo’s first team finished 6-23 overall, and 1-15 in the conference. He made some progress over the next few years, but not enough to make students and alumni happy.

Fortunately, Carlesimo had a new athletic director, Larry Keating, who understood how hard it was to build a successful program at the Big East’s smallest school in the Big East’s smallest gym. Keating asked him one night to make a list of what he needed to build a winner. Carlesimo came up with a list of 25 things. One of them was higher salaries for assistant coaches. Another was a full-time academic advisor.

Prior to the 1985-86 season, Carlesimo and his equally driven assistants had a great recruiting year. They landed three of the best players on the legendary Riverside Church AAU team: John Morton from The Bronx, Daryll Walker from Manhattan and Gerald Greene from Brooklyn. Because P.J. coached summer league basketball in Puerto Rico, he knew about this intriguing talent from Canovanos, Ramon Ramos. “I first met him in the eighth grade,” the coach says. “Just a great kid.” As it happened, Ramos was also an excellent student, and P.J. talked him and his parents into taking a chance on Seton Hall.

Even with those four freshmen, and 6-foot-9 sophomore Mark Bryant from South Orange, Seton Hall finished the 1985-86 season 14-18, 3-13 in the Big East. “I could feel we were getting better, though,” says the coach. Emblematic of that progress was Ramos. “When he first arrived on campus,” says Cunningham, “he could barely speak a word of English. But he picked up the language very quickly, and he never missed a class. He became an accounting major and by his senior year, he was a Big East Scholar-Athlete. He was a marvel.”

The next season, Seton Hall finished 15-14, which was good enough to make the NIT, the tournament that P.J.’s father had nurtured for so long. The team lost to Niagara, 74-65, in the first round, but at least the Pirates got a taste of a postseason tournament. Soaking it all in was a freshman walk-on from Seton Hall Prep, a Portuguese kid named Jose Rebimbas. “That whole season was a huge thrill for me,” says Rebimbas. “I learned lessons that I carry with me to this day.”

The Pirates added another local blue-chip talent for the 1987-88 season in Anthony Avent, a 6-foot-9 power forward from Malcolm X. Shabazz High in Newark. A 5-foot-3 guard named Pookey Wigington transferred in from Ventura (CA) College, where he was a JUCO player of the year. “It was either Kansas or Seton Hall,” says Wigington. “The Big East had great point guards, and I wanted to play against them.”

They were decidedly better. But for some ungodly reason, the Seton Hall student senate passed a resolution calling for the coach to be fired. The Big East essentially vetoed that resolution a few months later by naming him Coach of the Year. The Pirates finished the regular season at 22-13, and on Selection Sunday they found out they would be going to Los Angeles for the West Regional. After beating UTEP, 80-64, in the first round, they fell to the West’s No. 1 seed, Arizona, 84-55.

But the Pirates weren’t satisfied. “That summer,” says Wigington, “John Morton pushed us really hard. Three workouts a day. When your best player is that dedicated, you tend to follow.”

That was also the summer of the Seoul Olympics. Ramos happened to be playing for Puerto Rico, which lost in the opening game to Australia and a player Carlesimo had been after for years, Andrew Gaze. He had 33 points in the game, while Ramos had 11.

Gaze first came to Carlesimo’s attention after he scored 46 points in a 1986 exhibition game between Seton Hall and the Melbourne Tigers, who were on a tour playing against Big East schools. After that game, P.J. and assistant coach John Carroll tried to convince him to come to Seton Hall, but Andrew was already focused on the ’88 Olympics. Still, he was charmed by what he calls “the relentless pursuit of John Carroll.”

Says Gaze, “Every two weeks for two years, he just kept calling me and saying, ‘We think it would be really good for your development, and we’d love to have you here, and you could further your education, all those really positive things.”

After the ’88 Olympics, in which Team Australia made a strong showing, Carlesimo and Carroll gave it another shot. This time it worked: The 23-year-old Gaze really did want to further his education, and he had a comfort level with P.J. “It was one of the greatest decisions I’ve ever made in my life,” says Gaze. Rene Monteserin came to South Orange from a totally different place — South Catholic High in Hartford, Connecticut — with very different expectations. The son of an Argentine soccer star, he turned down a chance to play basketball or baseball at the Division III level because he fell in love with Seton Hall. “I figured basketball was out of the question since they had just been to the NCAA tournament.”

But because Seton Hall is a small school, word of how well Monteserin was playing in pickup games reached the basketball offices in Walsh. Assistant coach Bruce Hamburger let him know that he was welcome to try out for the team. At the end of the basketball tryouts, Carlesimo asked to see Monteserin. “I had no idea what he was going to tell me. He smiled and said, ‘Go call your high school coach. Tell him you’re going with us to The Great Alaska Shootout.'” If the Pirates were any good, they would find out right away in Anchorage right after Thanksgiving. Well, they beat Utah, 86-68, upset Kentucky, 63-60, and then overwhelmed defending national champion Kansas, 92-81, behind Ramos’ 16 points and Wigington’s seven assists.

“At that point, we felt we might have something special,” says Carlesimo. “The chemistry was good, we were deep and balanced, and Andrew (Gaze) fit in well right from the start.” Morton was especially impressed by Gaze. “It was like a long-lost cousin had moved in,” he says. “Make yourself at home. Here’s the kitchen, here’s the bedroom. This is your bunk.”

Cunningham, who knew her basketball, also saw their potential, although she was always careful about maintaining that she was there for their academic well-being. “I never hired a tutor who was a fan. I never talked about the games with the players. I was there to make sure they got good grades. I had occasional run-ins with P.J. when his practices cut into my study periods, but after every practice, he would hand out the index cards I gave him for each player, so they knew how serious he was about academics.”

Says Carlesimo, “I always tell people that the most important person in our program was Robin. Whenever we recruited someone, we never promised playing time. We did promise that they would graduate from one of the finest academic institutions in the country.”

The Pirates got off to a 13-0 record that included a win over No. 5 Georgetown in their first game in Meadowlands Arena. Suddenly, they were playing in front of 20,000 instead of the 3,000 at Walsh. But four days later, they went up to Syracuse and were blown out, 90-66. “A good wake-up call,” says Carlesimo. “For whatever reason, Syracuse had our number that year.”

Indeed, three of their six losses heading into the NCAA tournament came against the Orangemen, who beat them 81-78 in the semifinals of the Big East tournament despite 27 points from Morton and nine rebounds from Gaze. Other coaches would grumble that the Australian was just a mercenary from another country, but P.J. would counter, “Tell them to take a walk to Jersey City and take a look at the Statue of Liberty.”

Going into the tournament, Seton Hall was ranked No. 11 in the AP Poll. Fortunately, nemesis Syracuse was assigned to the Midwest Regional while the Pirates drew the West. That meant their first two games would be played in Tucson. The challenge for Cunningham was that there was still one week of classes before spring break, and the players had schoolwork to do. “P.J. and I were playing tennis one day, and I told him, ‘I think we need to bring in a math tutor.’ So, we did.”

They dispatched Southwest Missouri State and Evansville, two pretty good teams, to move onto the Round of 16 in Denver. But that meant they would have to face No. 8-ranked Indiana and P.J.’s mentor, Bobby Knight, and if they beat the Hoosiers, either UNLV or Arizona. “It was kind of like being back in the Big East again,” says Carlesimo.

They came up big. When they beat Indiana, 78-65, Morton says, “That was our stick-out-your-chest moment.” And then they rolled over UNLV, 84-61, and cut down the net. They were going to the Final Four… and Syracuse, which lost to Illinois in the Midwest Final, wasn’t.

After the Pirates beat the Runnin’ Rebels, Hamburger went running to catch a red-eye back to Newark because he had to scout the East Final, Duke vs. Georgetown, in The Meadowlands the next day. “We had been away for two weeks, so we were kind of in a bubble,” says Hamburger. “It wasn’t till I got back to Jersey that I realized how excited the people back East were about Seton Hall.”

The Final Four was in the Kingdome, but Larry Keating had arranged for the team to spend a few days in Los Angeles to relax, away from the media and hangers-on. Wigington was their tour guide. “Took ’em to the ‘hood,” he says. “I told them to ditch their blue Seton Hall clothes. Inglewood was Bloods territory. It turned into a great bonding experience.”

The cognoscenti were waiting in Seattle, waiting to see Duke turn Cinderella’s carriage into a pumpkin. Carlesimo wasn’t thinking that way, though. “We went 31-7 against a tough schedule. We didn’t do it with mirrors, but nobody seemed to know that. That was OK, though. If anything, it gave our players a chip to put on their shoulders.”

On the flight to L.A., he asked Cunningham if she wanted to hold a study hall before or after the Duke game. “Oh my God,” she thought. “He thinks we’re going to win.”

Nobody else thought that when Carlesimo had to call a timeout with Seton Hall trailing by 18, 23-5, early in the first half. He let the players handle the crisis themselves. In the huddle, The General (Gerald Greene) took over. As he recalls, “Basically, I told them, ‘We’re from New York City, we can’t let them do this to us.”

Wigington remembers it a little differently. “He was literally screaming at us. Focus. Stay together. And he hit us with New York City.”

Walker made a steal, and the newly energized Pirates were off, cutting the halftime lead to five, 38-33, and wearing down Duke’s best player, Danny Ferry. Greene proved particularly effective by driving to the basket and drawing fouls. (He ended up with 17 points, eight assists and a pair of Duke foul-outs — Quin Snyder and Christian Laettner). Seton Hall, in fact, was so dominant in the second half that Carlesimo was able to empty his bench in the waning minutes.

Even his walk-ons, Rebimbas and Monteserin, got into an NCAA semifinal, which is something they could carry with them the rest of their lives, along with their pieces of net from the West Regional. The Pirates had somehow flipped an 18-point deficit into a 17-point victory, 95-78.

We know what happened two days later.

Carlesimo says he hasn’t seen a tape of the Michigan game in 20 years. But he doesn’t need to. “I was mad about the foul call, but if I had to choose a crew, John Clougherty would have been on it. We had missed two key one-and-ones, and Rumeal — not a good free throw shooter — made both of his.

“Even then, we had three seconds left. But if you watch it, you’ll see that Ramon has no room on the baseline. Normally, he could take a few steps back, but there were too many photographers behind him, and Terry Mills was in his face … so he couldn’t arc the long pass. Still, our mindset was, ‘We got this,’ because we practiced that play after every shootaround all year. Daryll made a great effort, but it just didn’t go in.”

“I was supposed to catch it and pass off,” says Walker. “But I didn’t see anybody open, so I took the shot… man, it would have been a life-changer.” After the handshakes, the Pirates went back to the locker room, the losers’ locker room, to weep in private. “That’s where it hits you,” says Carlesimo. “The magical year is over.” He did the news conference, then went out to dinner with his parents.

The team was pretty quiet when they boarded the plane the next day for the long flight home. But when their plane landed at Newark that evening, the traveling party found a whole different party waiting for them: elated baggage handlers, pushy reporters, and the family members and friends they hadn’t seen in 21 long days. “We felt like America’s Team,” says Hamburger.

At around 10 p.m., a police escort took the bus back to campus as cars honked their approval. The players, many of them still wearing the cowboy hats they had been given in Denver, were ushered into the athletic center, where a stage had been set up and a Pirate Pride banner had been hung. Each of the players was asked to speak to a crowd of about 2,000, and when his turn came, John Morton made sure to thank Robin Cunningham for her guidance. “That meant the world to me,” she says.

“This basketball team is your basketball team,” Carlesimo told the crowd as he handled the trophy that now sits outside Walsh Gym. “Always feel as good about Seton Hall as you do right now.”

THEY held a more formal parade for the team a few days later. There was another cause for celebration in June when John Morton was chosen in the first round of the NBA draft by the Cleveland Cavaliers as the 25th overall pick. Andrew Gaze returned to Australia to play for the Melbourne Tigers. Ramon Ramos wasn’t drafted, but the Portland Trail Blazers, who already had Mark Bryant, signed him as a free agent.

In early December of ’89, Robin Cunningham got a call from Ramos, who was on the injured list because of tendinitis in his knee. “He wanted me to send him his accounting books,” she says. “He was studying for his CPA exam.”

Ramos had been cleared to play and was just waiting for his chance. But on Dec. 16, while coming home from a birthday party for Mark Bryant, he lost control of his car on an icy patch of Interstate 5 south of Portland. Carlesimo got the call on a Friday night before a home game against his alma mater, Fordham, in the Meadowlands. Ramon had suffered a traumatic brain injury. Somebody had to call his parents in Puerto Rico, and that somebody was P.J.

“The prognosis wasn’t good,” Carlesimo recalls. “They did not think he was going to live. We debated whether to play the game or not, and ultimately decided to play. It was the worst game I’ve ever been involved in. We lost, but it wasn’t the score. It was because of the despair. He was the most popular player on campus… with faculty, students, workers. The feeling was palpable.” Carlesimo flew out to Portland the next day to be with him and his parents. Ramos was in a coma for three months. When he came out of it, he couldn’t walk because he was paralyzed from the waist down, and he couldn’t really talk. He could only access his short-term memory. In the spring of ’90, a Seton Hall contingent that included former teammates Morton and Greene, as well as Carlesimo and Cunningham, flew out to visit him.

“We were in his hospital room,” Carlesimo says, choking up a little, “and his mother asked him, ‘Who are these people?’ The neurosurgeon who had been with him for six months was there. Well, Ramon starts pointing to people. And he says, ‘Robin, John…’ He goes around and identifies everybody. I looked over at the doctor, and he was crying.”

Ramos was also beginning to walk. “Despite Hazards Move Forward.”

Carlesimo took Seton Hall to four more NCAA tournaments before leaving for the NBA and the Portland Trailblazers in ’94. Three years later, he was coaching the Golden State Warriors when he had a little run-in with Latrell Sprewell. Enough said. Carlesimo has been a missionary for basketball his entire life, either as a player or a coach or a broadcaster. When John Clougherty was inducted into the North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame in 2015, P.J. applauded the loudest. When he sat behind fellow broadcaster Andrew Gaze in the press box at the Summer Olympics in Rio, he kept wadding up stat sheets and tossing them at the head of his one-time star. Nowadays, he lives in Seattle, which is as good a place as any for a man who left there 30 years ago with his head held high.

John Morton played three seasons in the NBA and holds the distinction as the last Cavalier to wear No. 23 before LeBron James arrived. He became something of a basketball gypsy, playing everywhere from Rapid City to Andalusia before turning to coaching in 2006. There’s something nice about him coaching at Saint Peter’s with another former Pirate, first-year coach Shaheen Holloway, and an AD, Bryan Felt, who not only went to Seton Hall, but also wrote, produced and directed “Band of Pirates,” a wonderful DVD that celebrated the ’89 team upon its 20th anniversary. “The Peacocks finished 10-22, which is a better record than Carlesimo had his first year at Seton Hall.

Jose Rebimbas also became a coach, leading the William Paterson Pioneers to nine NCAA Division III tournaments in 20 years before he had a falling-out with the school. (His players protested his firing by walking off the court right before the next game.) He is now the assistant coach for the women’s team at Seton Hall. His fellow ’89 walk-on, Rene Monteserin, lives in Hartford, works as an underwriting manager and loves watching his three teenage sons play soccer. Bruce Hamburger will be going back to the Big Dance as an assistant for Fairleigh Dickinson, the Northeast Conference champ.

Pookey Wigington, a marketing major, returned to L.A., started representing athletes and comedians and now manages actor-comedian Kevin Hart. Last week he rejoiced when sons Snookey and Tookey each won a state high school championship. “P.J. called to congratulate me,” he says. Right behind them are Wookey and Zookey.

As for Ramon Ramos, he lives a full life with his parents in Puerto Rico and keeps in touch with his Seton Hall teammates. Asked recently what his memories were from that season, he says, “I remember the practices. Instead of taking it easy, we practiced very intensely… it was a strong team… Andrew Gaze, I remember him. He was a great shooter.”

There’s another YouTube clip worth watching. This one is from 2006, when Ramos returned to South Orange to be inducted into the Hall of Fame.

Carlesimo introduces him by saying, “Every place that he’s been has been better for his presence. And tonight, going forward, the Seton Hall University Hall of Fame is a better place because of this gentleman.”

After years of physical and speech therapy, Ramon takes the podium dressed in a tux and tells the audience, loud and clear, “I want to share this with my teammates.” Watching him, you can feel both the resolve of one huddle, and the brotherhood of another.

Seton Hall’s run to the Final Four in ’89 was a once-in-a-lifetime experience. But it is interesting that 30 years after the Pirates won the hearts of basketball fans, this year’s team will play in the Midwest Regional, against Wofford in Jacksonville, armed with a center from the Caribbean, Romaro Gill of Jamaica; a John Morton-esque guard in Myles Powell, and a coach, Kevin Willard, whose father (Ralph Willard) was a legendary coach.

Hey. You just never know.

Powered by WPeMatico